This post concerns the year, 1937, in Paul’s life, just after he got his diploma in engineering and architecture from the Swiss Federal Technical University in Zurich. He went to London to look for a job. The chapter develops the seed of the story that was planted earlier in this blog, PAUL AND LÁSZLÓ MOHOLY-NAGY.

In my interview with my father he confessed that after five or six weeks in London he was at his wit’s end. He sat on the bed in his boarding house room at 3 Bedford Square and leafed through the pages of the London telephone directory. Having nothing else to do he occupied himself with a pencil, filling in the “o”s in people’s names. He came across a name with three “o”s, László Moholy-Nagy. It was a Hungarian name which Paul had heard before – someone, it seemed, involved with design.

Paul didn’t telephone. He figured his chances were better if he showed up in person. So he wrote down the address and spent his last pennies to take the tube from his lodgings near the British Museum to the Belsize Park station in Hampstead. From there he walked to the building in which Moholy lived that looked “just like a giant ocean liner which ought to have a couple of funnels.” My father relates:

I rang the bell and he said: “What do you want?” I said: “I’m Hungarian!” And he slammed the door in my face. Then he must have felt embarrassed and he opened it and again said, “What do you want?” And I said I was looking for work. And he said, “Well, what do can you do?” And I said I was the best draftsman in the whole world and he said, “Well, come back after lunch.” And then I walked around for two hours and came back and he gave me a job.

My father’s life would have turned out quite differently had he not had the great good fortune to discover Moholy in London and then act on his instinct. Between the young man and the older one there was a shared cultural experience and a way of facing the world with a mix of defiance and optimism.

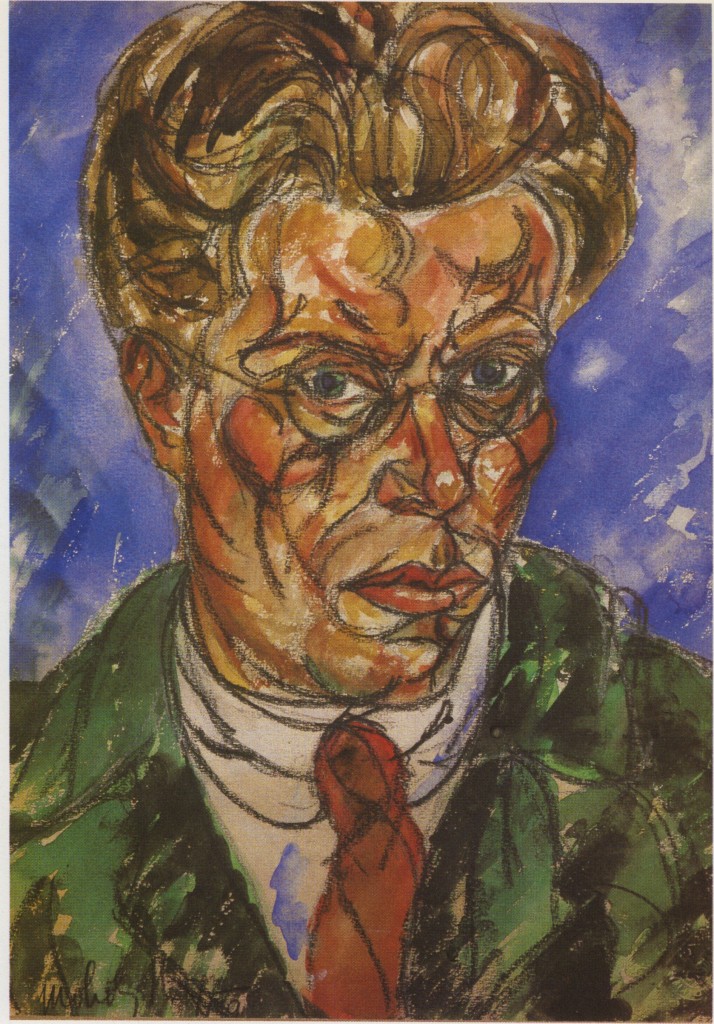

Moholy was a 20th century renaissance man, versatile, charismatic, and accomplished in many fields, though he would have hated the term renaissance because it derives from an historical period. By the time Paul knocked on his door Moholy already had an international reputation as a painter, sculptor, typographer, designer, photographer and filmmaker. He was also an essayist, lecturer, and social critic.

For five years, in the 1920s, Moholy taught the foundation course at the Bauhaus School in Germany. Out of the school grew a philosophy, a way of approaching issues in art, craft, design and architecture, that reverberated throughout the 20th century. The 1919 founding proclamation of Bauhaus was the modernist’s call to arms:

Let us then create a new guild of craftsmen without the class distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist! Together let us desire, conceive, and create the new structure of the future, which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity and which will one day rise toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.

Moholy collaborated with Bauhaus founder, the German architect Walter Gropius, on fourteen books which applied their philosophy to the entire range of creative and productive endeavors. Stating this philosophy Moholy wrote:

A human being is developed only by the crystallization of the sum total of his experiences. Our present system of education contradicts this axiom by stressing preponderantly a single field of application. Instead of extending our milieu, as the primitive man was forced to do, combining as he did in one person; hunter, craftsman, builder, physician, etc., we concern ourselves only with one definite occupation – leaving unused other faculties.

Moholy exhorted his students not to be intimidated by “tradition and the voice of authority” or specialists, who, “like members of a powerful secret society,” obscure the path to authentic individual instinct and creativity. This was balm to young Paul’s soul. He had audaciously thought of himself as an artist, a poet, a social activist, an architect, and an engineer. After his struggle with the career-track dictates of the Swiss polytechnic, the Bauhaus view of the interrelatedness of art and technology was profoundly liberating.

There were other things, experiences that had shaped Moholy’s life, which seemed synchronous, yet different from the Weidlinger family history. Like my grandmother Julia, Moholy had become gravely ill in the great flu epidemic of 1918 but he had survived. Like my grandfather Andor, Moholy had been a soldier in the Great War. Unlike Andor, Moholy had experienced the carnage of the battlefield. Using colored pencils and crayons he sketched intimate scenes of life in the trenches on the backs of military-issue postcards. He made portraits of peasants in their fields in Galicia and of his wounded comrades in hospitals.

Sergeant Moholy-Nagy’s postcards echoed the creative voices of socially concerned Hungarian artists, writers, and photographers that had turned their attention to the plight of their nation’s dispossessed. It’s not surprising then that right after the war Moholy joined the communist party and supported Béla Kun’s Hungarian Soviet Republic.

To the clandestine communist youth movement in Budapest (which Paul belonged to until he was arrested at the age of sixteen) Moholy would have been an icon. It was precisely his fellow travellers, Hungarian Communists who had fled to Moscow (and who, in 1932, had made the mistake of returning to Budapest) that my father and his schoolmates were petitioning to save from execution. Fortunately Moholy had fled to Vienna. Otherwise he would most certainly have been killed in the White Terror, the monarchists’ counter-revolution.

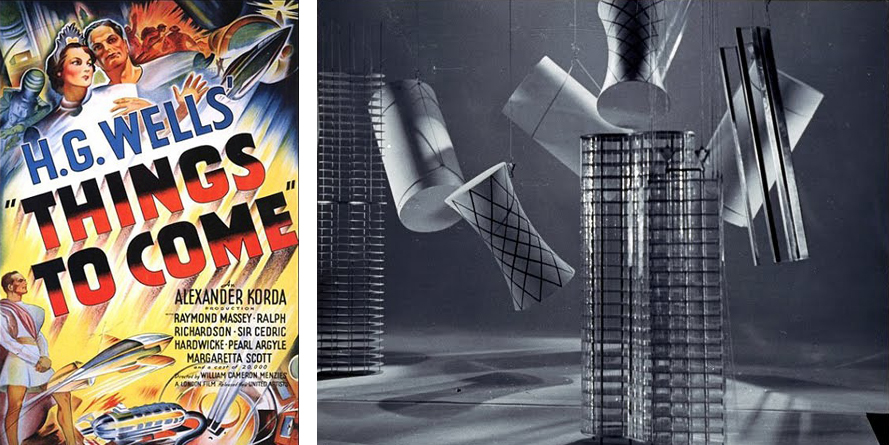

Another synchronicity is that Moholy had worked on special effects for a science fiction movie produced by our putative relative Alexander Korda. Based on H.G Well’s The Shape of Things to Come, the film depicts an alternate world history, diverging from reality in the 1930s and ending in the year 2106. A devastating plague wipes out most of humanity but out of the civilization’s wreckage a fraternity of mechanics and engineers create a utopian world. I can see Paul taking pleasure in the idea of a utopia built by mechanics and engineers.

For all these reasons, when Moholy opened the door of his London flat to my father in March 1937 there was a mutual feeling of déjà vu; a recognition of shared history and ideals. Paull had found a mentor. He wrote to his cousin Ilona Rádo:

I am starting to again hope. Moholy is so unbelievably kind. I really like working for him, although his studio is a madhouse. It is full of fantastic pictures, and models. Moholy himself puts his sentences together in three languages: Hungarian, German, and English, and so it is very difficult to understand his complicated thought processes. Despite this, I consider him an exceptionally smart person. What is truly unique: He is also exceptionally honest. I am only now beginning to see how well known he is. He just had an exhibit of his paintings in London and one at the constructivists’ exhibit in Basel. Just yesterday, he was invited to give a lecture in Oxford. Meanwhile, he makes films, designs posters and exhibits, and works on his inventions.

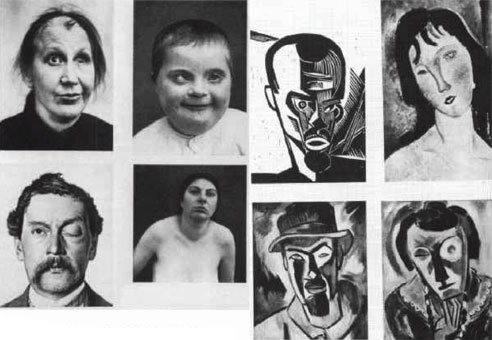

Moholy was a refugee from fascist Germany. In 1934 he had been ordered to submit three of his paintings for censorship to the Reich’s Chamber of Culture. 1935, when he arrived in London, Nazi denunciations of modern art and architecture reached their height. The fascists mounted “instructive” exhibitions in which modernist paintings were hung next to photographs of deformed and diseased human beings. The message was: “Modernism is a sickness.”

I wonder if this is what Paul’s poem, “The Ballad of The Sick,” the subject of an earlier post, is all about. It could be more than just adolescent nihilism.

… but they [The Sick] just hate in secret

as their souls grow cold, their blood goes white,

panting for vengeance against the great society of the Healthy.

The secret organization of the Sick will rise up,

And throw a bomb amid The Healthy.

Crutches will turn into rifles, thermometers into bayonets

Sickbeds will become tanks and their dying desires will be reborn…

Whatever the case, once Paul got the job with Moholy he didn’t have much time for poetry or politics. He worked as a draftsman on commercial projects. At that point Moholy was designing posters for the London Transport System and window displays, modernist dioramas, for the men’s clothing store, Simpson’s of Piccadilly. There was also a commission from a travel agency, which Paul was immediately put to work on.

He [Moholy] had this idea of making a big head out of neon and out of the brain these ideas would come… of travel. He came to me and said, “Well Master Pál, I want you to draw a brain machine now.” Then he walked out. I was so depressed because I thought, Jesus Christ, everybody probably knows what a brain machine is except I. Kepes was sitting across the room and he was laughing!

(György Kepes, another Hungarian, became a life-long friend as well as a famous design theorist.)

Paul had been working for Moholy for about three months when he wrote an incredibly long and convoluted letter to his fiancé, Madeleine Friedli, who would become my mother. He made several drafts, which is why it’s one of the few letters he wrote to her that has survived. It is a manifesto on beauty and art.

My little darling, here is the letter I promised you. It was an easy promise to make, but I don’t think it will be so easy to keep it. I want to tell you all of my thoughts on Beauty and Art so that you will give it as much thought as I have and then tell me later whether or not you agree with me. I want to approach things the way one would a revolution; by this I mean tearing down the old — whether it be buildings or ideologies — and then constructing a new world in the ruins.

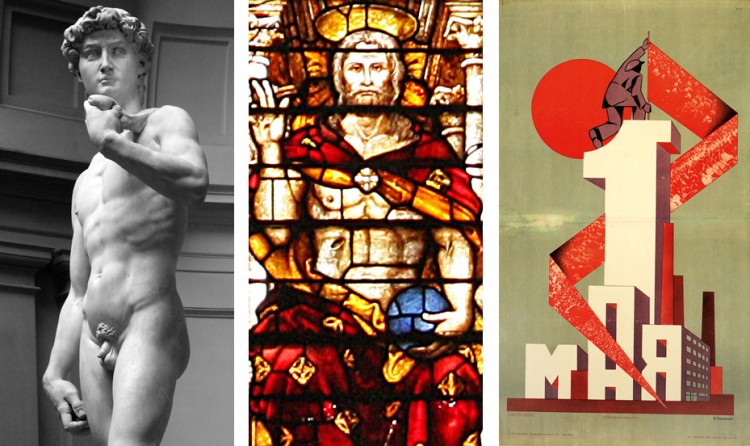

There follows a passionate treatise in which twenty-three-year-old Paul denounces Plato and Kant as the allies of bourgeois capitalists. He rejects the idea of a Divine Constant, underlying all that we perceive as beautiful. He offers, instead the Marxist view that beauty is only an idea that stems from the ideology of a particular time and place. This is important because those who shape the ideology of an era, writers, artists, and architects, can enlist art in the service of that ideology and, in so doing, guide the world towards a brighter future. Wading through the dialectic twists and turns of my father’s arguments I imagine a cartoon in which a classical Greek sculpture (representing Timeless Beauty) and a cathedral’s stained glass window (representing the Divine Constant) give way to visuals of the sleek functionality of the industrial age, culminating in an apotheosis of Soviet Constructivist propaganda posters.

To use one of my father’s favorite words there is something touchingly naïve about his letter, as if the entire history of mankind’s creative endeavor could be summed up so simply. Yet it is important to understand that Paul is writing to his beloved in a time of manifestos; increasingly urgent calls to action as the shadow of fascism spreads across Europe. There was nothing that was not political; not art and not beauty. In Europe of the 1930s there was no space in which to be simply “an artist” or “an architect.”

Paul’s mentor, Moholy-Nagy, echoes this in his own writings. To Moholy machines are beautiful, and it is from them one should take inspiration because of their pure functionality. There is also a rationality to machines that efficiently do the work they are designed to do; a sewing machine, a water pump, a locomotive… Their simple predictability was a comforting antidote to the social dysfunction that appeared to be tearing the world apart. Moholy, writing in the journal Today: Activist Art and Social Issues, declares:

To be a user of machines is to be the spirit of this century. It has replaced the transcendental spiritualism of past eras. Everyone is equal before the machine. I can use it; so can you. It can crush me; the same can happen to you. There is no tradition in technology; no class-consciousness. Everyone can be the machine’s master or its slave.

This is the root of Socialism, the final liquidation of feudalism. It is the machine that woke up the Proletariat…. This is our century: technology, machine, socialism. Make your peace with it; shoulder its task….

Then there is art, the language of the senses. Art crystallizes the emotions of an age; art is mirror and voice. The art of our time has to be fundamental, precise, all-inclusive…

Rebecca Johnson

August 19, 2019 at 1:51 amThank you for your writing, in particular I ponder this passage “Paul is writing to his beloved in a time of manifestos; increasingly urgent calls to action as the shadow of fascism spreads across Europe. There was nothing that was not political; not art and not beauty. In Europe of the 1930s there was no space in which to be simply “an artist” or “an architect.” No space to be simply “an artist or architect! Apropos of our time.

I was just introduced to your blog by Pat Ferrero, a good friend up here in Mendocino. I actually met you perhaps 50 years ago, my parents Phil and Ilse Johnson were friends of your mother Madeline. Your mother introduced our family to the sluice way between Higgins and Gull ponds. This is still a place I visit today. You took me sailing on Higgins when I was about maybe 10 or 12. Also another visit I rowed your rather precarious blue dinghy. Perhaps some day we can meet again. I am a sculptor and painter in Mendocino. A good message for our time there is no space to be simply an artist. Thank you for your writing, intriguing story about your father and the fascinating people he knew.