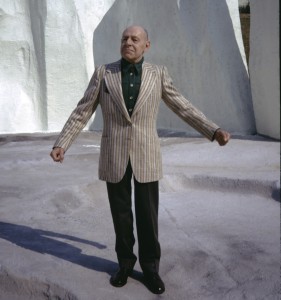

Among the boxes I received from my family upon my father’s passing there is one that contains several bulging folders of correspondence, both personal and professional, with the French artist Jean Dubuffet. The fact that these folders were in my father’s personal files, rather than in the archives of Weidlinger Associates, is significant. Dubuffet was a special person in Paul’s life and there are many affectionate notes between them. Some from my father are signed “Love, Paul.” My father loved artists and he loved Dubuffet the most because of his quirky, playful and fiercely iconoclastic nature.

One of the most famous painters and sculptors of the second half of the 20th century, Jean Dubuffet had an idealistic approach to aesthetics. He embraced so-called “low art” and eschewed traditional standards of beauty in favor of what he believed to be a more authentic and humanistic approach to image making.

I want my street to be crazy, I want my avenues, shops and buildings to enter into a crazy dance, and this is why I deform and distort their outlines and colors…

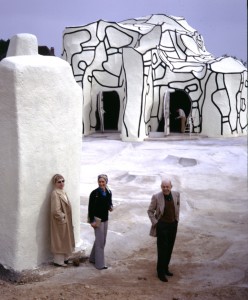

Starting in the late 1960s the artist began to create large sculpture-habitations within which people can wander, stay, and contemplate. Paul did the structural engineering for Villa Falbala, a building without straight lines or square corners. Paul also did the engineering for Four Trees, a monumental work that stands in the Chase Plaza in New York. Paul held Dubuffet in such high esteem that he did a significant part of the consulting pro bono, undoubtedly to the chagrin of his partners at Weidlinger Associates.

Starting in the late 1960s the artist began to create large sculpture-habitations within which people can wander, stay, and contemplate. Paul did the structural engineering for Villa Falbala, a building without straight lines or square corners. Paul also did the engineering for Four Trees, a monumental work that stands in the Chase Plaza in New York. Paul held Dubuffet in such high esteem that he did a significant part of the consulting pro bono, undoubtedly to the chagrin of his partners at Weidlinger Associates.

Paul also became involved in the movement to support the artist against the giant French automaker, Renault. In 1975 the new president of Renault halted construction of the Salon d’Eté, Dubuffet’s most ambitious sculptural landscape. The work, in the courtyard of Renault headquarters, had been commissioned by the company’s prior president; but, it was slated for demolition when only half-completed. Dubuffet fought the razing of his work… proclaiming intrinsic rights of artists. He lost his quixotic battle in the French courts but a community of artists and intellectuals had rallied around him. My father was among them, reaching out to contacts at the New York Times and the New Yorker Magazine to generate press in support of the work.

My father continued to correspond with his friend until the artist’s death in 1985. Sometime during their long association Dubuffet presented Paul with a large box of fanciful playing cards which the artist titled: Banque de L’Hourloupe, Cartes à Jouer et à Tirer (Deck of the Hourloupe, Cards for Playing and Dealing). Hourloupe is a word invented by Dubuffet inspired by the words hurler (to shout), hululer (to howl), loup (wolf) as well as an old French folktale Riquet à la Houppe. On the inside cover of the box containing the deck the artist has written:

Our words – mirages of solid things, repositories of temporary combinations of thought which give us the illusion of carving up an uncarvable world… we are now going to translate them into playing cards, muddle them up, and then rearrange them in a different order; we will shuffle them and deal them back on the table of the spirit to make it fresh and green again…