My father was part of a group of thirteen Hungarians Jews who had been classmates at the German Technical institute in Brunn. They all immigrated to Bolivia in 1939 and 1940. They called themselves “The Gang of 13.”

Arriving in La Paz they immediately put into practice their idea of a utopian communist community. They lived together in a boarding house and shared both their earnings and household expenses. Paul told me: “It was quite a lovely boarding house with big windows and a balcony overlooking a main street.” I have a photograph of seven men in their pajamas on the back stoop; they are all polishing their shoes, sharing a tin of shoe polish.

Arriving in La Paz they immediately put into practice their idea of a utopian communist community. They lived together in a boarding house and shared both their earnings and household expenses. Paul told me: “It was quite a lovely boarding house with big windows and a balcony overlooking a main street.” I have a photograph of seven men in their pajamas on the back stoop; they are all polishing their shoes, sharing a tin of shoe polish.

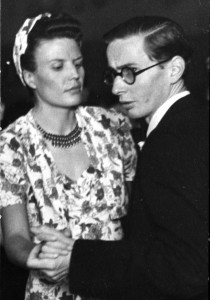

My father started using Paul as his first name, instead of the Hungarian Pál. When my mother, Madeleine arrived she was welcomed at the boarding house. Though my parents regarded wedlock as a petty bourgeois institution, they got married in a civil ceremony. Bandi and Jancsi served as witnesses. “It was over in about ten minutes,” said my father. “After we went out for a cup of coffee.”

Over time the arrival of women in the young men’s utopia changed things. Imre Erdős, who chronicles the adventures of the Gang of 13 wryly observed that on laundry day if a man ended up with the same number of underwear that he had put in it didn’t matter who the original owner was. But one could hardly expect women’s stockings to be accounted for in the same way. Couples moved out and the men who remained single debated placing an ad in a Budapest newspaper that read:

WIVES WANTED. Men living and working in South America are looking for Hungarian wives. Only healthy and work-loving women need apply. Send applications with a photograph, round trip ship tickets and the code phrase: “everything will turn out OK in the end.”

Paul’s story is interwoven with the exploits of the Gang of Thirteen. Paradoxically he is both integral and peripheral. He participated in the life and business of the commune yet he had his own apartment and his job with the construction firm, Soconal. The latter was crucial. The Soconal desperately needed reliable sub-contractors; electricians, plumbers as well as pre-fabricated windows and doors and the carpenters to install them. So the Hungarians founded their own company, Compañia Nacional Alfa, that could meet these needs and Paul made sure that Soconal’s business went to them.

I have some invoices with Alfa’s beautiful logo depicting a pitched roof with the Greek letter alpha (d) framed between the rafters.. Alpha: First in order of importance. An audacious name for a company that started out with odd carpentry jobs.

I have some invoices with Alfa’s beautiful logo depicting a pitched roof with the Greek letter alpha (d) framed between the rafters.. Alpha: First in order of importance. An audacious name for a company that started out with odd carpentry jobs.

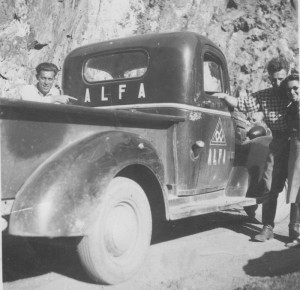

Paul said: “The boys worked full time and I worked at night with them and we had great fun at the beginning.” A bookshelf, a wardrobe, a table with wheels, and an antenna installation are some of the items on the first invoices. The work was done in a rented apartment with a few tools brought from home. As the business grew it was possible to acquire more tools and a real workshop. A picture shows the boys posing with Alfa’s first truck. On Sundays the whole gang piled in for excursions to La Titicaca which, they discovered, was too cold for swimming.

Paul said: “The boys worked full time and I worked at night with them and we had great fun at the beginning.” A bookshelf, a wardrobe, a table with wheels, and an antenna installation are some of the items on the first invoices. The work was done in a rented apartment with a few tools brought from home. As the business grew it was possible to acquire more tools and a real workshop. A picture shows the boys posing with Alfa’s first truck. On Sundays the whole gang piled in for excursions to La Titicaca which, they discovered, was too cold for swimming.

The company grew quickly. The carpentry shop made doors and windows. Then it was decided to make metal-framed double-glazed windows, better suited to the Bolivian climate. Templates were obtained from America, the boys taught themselves how to weld, and production started. A building inspector threatened to shut down the operation, claiming the workshop was unsuitable for window production but he was mollified when Erdős repaired his wife’s cooking stove. In general Alfa was well received. Erdős wrote:

There was this perception: ‘Let’s trust them, that they can do everything, they are European engineers!’ We would have caused disappointment if we turned down a project with an excuse that ‘we can’t do it.’ It is true that there was a wide variety of engineers within our “Gang of 13.”

A vivid recollection of Alfa’s exploits shared by Paul and by Erdős is the story of a electrical generator that the company contracted to provide to a client – outbidding the big American company, Westinghouse. Paul’s and Erdős’ accounts vary somewhat. My father boasts that the generator was destined to power the entire town of Copacabana. Erdős gives the more plausible scenario that it was destined for a hotel within the town. Erdős writes:

On the shores of Lake Titicaca where young Bolivian married couples went to ask the Virgin to give them healthy children, a hotel was built. Alfa was hired to provide the electricity. We asked companies for bids to provide a generator, but they were extremely expensive and could not be delivered on time. So we looked for a used one.

Paul, continuing the story, said:

One of our guys (Pista Roth) was a born wheeler-dealer and he went out and he found a huge diesel generator in little pieces. He bought it for two hundred dollars, which was pretty much ALFA’s entire operating capital, and he piled it in our truck. He said, “Look what I bought for two hundred dollars! We can compete with Westinghouse if we manage to put this together!”

“Then,” says Erdős, “we started the ugly work of assembly and repair.” It’s typical that the boys were confident that they could fix the huge machine though no one had actually ever repaired a generator before.

The pressure was on. The hotel that had contracted for the generator had invited government ministers and the Mayor of Copacabana to a ceremony at which the lights would be turned on. “We spent many nights trying to put this goddamn diesel engine together,” said my father. “And we finally did, but we couldn’t get it started. I remember you needed compressed air to start the generator and there was just one compressed air factory in town and we used to buy their total output day after day.” A cloud of despair settled over the Alfa team. One of the boys, drowning his sorrows in a pub, recounted the tale of woe to a man on an adjacent barstool. The man was a diesel mechanic. Paul says:

We brought him to where we were working. This guy saw the engine and tears started streaming down his face. He said, ‘This is my diesel engine. I used to supervise this.’ And he went to the engine and fiddled around and it started and we delivered it.

Erdős continues:

After desperate work the machine was ready on the day of the grand opening. We held our breath and turned it on. The hotel lit up. Everything was fine. Then there was a huge crash and everything went dark. The timing belt had snapped. We fixed it and five minutes later the lights we back on. Fortunately the official guests had not witnessed the embarrassing mishap. They were all still in church for the blessing of the hotel.

The lights stayed on long enough for all the guests to retire to their rooms and then they went dark for good. Erdős observed: “The wiring of the building was so full of shorts it was not reparable.” Fortunately the blame was not pinned in Alfa as it had not done the wiring.

The common quality of Paul’s and Erdős account of the adventures of the gang is one of insouciance and careless good fortune. Lucky things just kept on happening. The men actually worked incredibly hard to make a life in Bolivia but downplayed their efforts. Certainly there were hard times but to make much of them seemed in bad taste. Self-pity was the greatest sin. The words my father wrote in is journal as a teenager still resonated: “Woe to the defeated, because he feels defeated.”

Keeping a low profile was another part of it. Never did the Gang of Thirteen identify themselves as Jews or as communists. They could have savored a taste of the old Austro-Hungarian empire at one of many German/Jewish establishments opened by émigrés in La Paz. But they avoided them.

At the end of 1939 a virulent wave of anti-Semitism swept through the country when it was discovered that Bolivia’s foreign minister had colluded with consular officials in European capitals to sell thousands of immigration permits to Jews, pocketing millions of U.S. Dollars. The timing of Bandi’s purchase of visas for the gang of thirteen at the Paris consulate corresponds perfectly with the period in which the minister Eduardo Diez de Medina and his cronies where raking in the cash. When Medina was put on trial in La Paz spectators in the galleries kept up a steady chant of “death to the Jews.” A bill was introduced in the Bolivian congress to expel all Jews from the country stating that “Jews are an unhealthy element due to their selfish social, racial and moral principals.” The newspaper La Calle, in one of its editorials supporting the bill, lamented the “inundation” of the country by people “with very beaked noses” – members of the Jewish race who were waiting to fall like a ravening horde on the cities of Bolivia.”

The closest that Erdős comes to dropping his jocular tone when writing about his friends and implying their collective vulnerability is when he observes:

About 100 Hungarians live in La Paz. It is like a small town back home, only worse. People are much too eager to know each other, and too many are full-time gossips. This is not the case with us. I was often surprised when, upon introducing myself, one would say: “You are that Erdős ?” Certain individuals have a lot of free time. We don’t have much of a social life, because apart from our own company we keep in touch with other Hungarians quite sparingly. We don’t need more company as there is plenty of us, and among others there are just a very few people that have similar social and [communist] political views.