While apprenticed to the famous architect Le Corbusier in Paris, Paul struggled to formulate his own ideas on architecture, amid the cacophony of theories and slogans being bandied about by Modernists. Scribbling in cafes and on park benches, on long summer evenings and weekends, he wrote a rambling manifesto. Its introduction is a call to battle, rising to a crescendo of righteousness.

“After much study and little experience, one already has a few thoughts about architecture and enough qualifications to express them. Perhaps the soft voice of the inexperienced may now be allowed to join the deep bass voices of the authorities? After you have heard it, you will say: this voice is dissonant! Possibly! But it is after all a very soft voice and does not wish to disturb.”

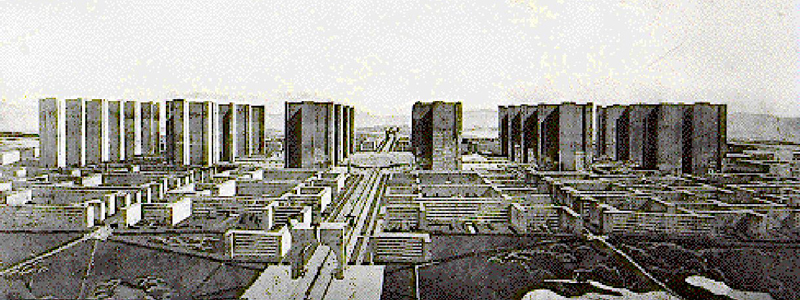

“We see the starkest struggle of two irreconcilable worldviews in the history of people. Victory belongs to an advanced movement, far-reaching and battle-tested, which is built on thinking freed from useless traditions. But it is not yet definite. Our buildings that reach for the sky, our airy constructions, our bridges that float bravely over their gorges – a “harsh reality” could still shatter them all. Then, instead of sunlit houses rising up out of the ruins, we might find dark cellars and palaces bursting with gold and silver. We must, as never before in history, feel our bond in this struggle along with the compulsion to take a stance.”

Though Pál shared with Le Corbusier the idea that architecture could improve, even save society, he questioned the architect’s vision for mass-produced housing. He rejected the creed, that: “A house is a machine for living.” Working out his own theory in juxtaposition to Le Corbusier’s, he comes up with an idea that is both transcendent and truly radical for its time – but he only comes to this idea at the end of a long and tortured journey.

To begin with, Pal is trained to write in the incredibly long-winded and obsequious German academic style in which one must make bow, scrape and tip one’s hat to every recognized theory in the field before making one’s own modest contribution to the discourse. Pál was naturally influenced by Marxist thought and by the modernism of his mentors, Moholy Nagy and Le Corbusier, but his is also deeply enmeshed in the anti-philosophical philosophical movement of Logical Positivism.

The Logical Positivists (known also as the Vienna circle) were a humorless bunch that wanted to “erect a unified structure of science in which all knowledge would be built up from logical strings of basic experiential propositions.” According to Logical Positivists language should be cleansed of “ornaments,” all metaphor and subjective impressions. Each sentence should be “proven.” This anti-philosophy had had a huge impact on the disciples of the Bauhaus school of architecture. A new house should be purely the product of rational science(s), the synthesis of work done by economists, statisticians, hygenicists, climatologists, and engineers. The architect became a kind of rationalist traffic cop, concerned with organization and coordination of the myriad disciplines brought to bear on the problem of creating a dwelling for human beings.

Pal lays out this view but then challenges it.

Let us build a building with a floor plan that works well; its construction is perfect, it’s colors and it proportions are pleasing. It can be a model for mass production. Experts do the design, builders erect the structure, and “artists” are brought in to beautify it. This is familiar, we know it well. We also know and that it is not right. The result is merely a concatenation of rooms. There is something missing. What is missing is the creation of space (Raumgestaltung).

What is this “creation of space” that young Pál insists is an essential part of the package? In attempting to define it he goes to great lengths to avoid using un-provable subjective language; language that is unacceptable in system of logical positivism. Yet he finally surrenders and declares: “The only common characteristic in the creations of modern architecture is a highly enhanced level of spatial experience; a joy of space. In architecture we experience relationships in space. This experience is both active and passive at the same time: We move through the space and experience its effect upon us. The clearest form of spatial experience is dance. It is space creation done with the simplest methods.”

Three simple words: joy of space. A mysterious experience that defies measurement, classification, and deconstruction. It is one thing to build a house that is perfectly functional. It is something else to build a house that is perfectly functional and, at the same time, elicits a sense of well-being and joy through the arrangement of its volumes. This is something that industry cannot produce, something that requires the spatial intuition of the architect responding to a unique set of circumstances. It follows that architecture is more an art than a science; since it must relate and respond to unquantifiable human experience.

Pál concedes that some “prototypical characteristics of humans can be defined but individual instances do not always conform to collective definitions.” Therefore “the architect must always deal with the individuum (from Latin, meaning the unique, individual instance). In fact it seems unlikely that architecture will ever become an exact science.” Therefore the architect will always have a significant role.

Pál seems almost apologetic that, in the end, architecture cannot be described as a pure science; a conclusion which would be so much more compliant with the absolutist anti-philosophy of Logical Positivism or the pure machine-inspired functionalism of Le Corbusier’s house as a “machine for living in.”

With his words, joy of space, Pál distinguished himself as a young man capable of thinking outside the box.

Chuck Wolfe

February 18, 2019 at 3:57 amMass produced machines for living cover our landscape here now. I think functional servitude came first but the endless repetition serves the master of profit now. Not just the tract homes but even the McMansions become boringly humdrum conforming to a profitability model.

Pierre Ravaçon

November 24, 2018 at 4:39 pmincredible insight, to see past the period infatuation with the “machine for living.” Too many others got stuck in its trap.