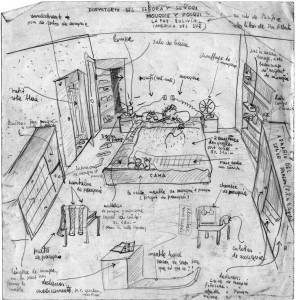

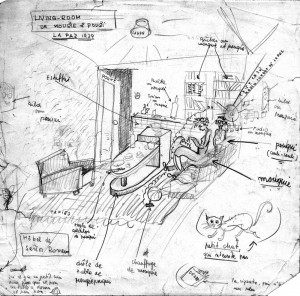

I am in possession of two curious drawings made my by father in late 1939. They are cartoon sketches of Pouqui and Mouqui, the love names my parents gave each other. The drawing shows them settled into their apartment in La Paz, Bolivia. Furniture and personal effects are carefully labeled in French. By naming these things my father is claiming a new life, a dramatic improvement over his hand-to-mouth existence while apprenticed to Le Corbusier.

In the bedroom sketch the big double bed is labelled “a project of Pouqui.” The mattress and blankets have been purchased for 500 bolivianos. In the bedroom my mother’s tiny handbag contains “lots of money” and both my parents’ clothing is strewn on the floors and furniture. Mouqui’s lingerie is contained in a wardrobe drawer… but there is so much of it that the drawer cannot be closed.

In the living room sketch Pouqui, with his big round glasses, listens to Radio Condor from La Paz while Mouqui hunches over the typewriter she brought from Zurich. She is seated close to an electric heater identified uniquely as hers. There is a mysterious piece of furniture (“no one knows what it is for”) and an imaginary cat.. My father’s sketches are a joyous boast that seems to proclaim: “Look we have become normal!”

How did my father come to wed my mother? And how did they come to be living in La Paz in 1939? These stories belong to the offline iterations of The Restless Hungarian, a film and a book, but suffice to say that my father, a Jew with an arrest record (for communist activities) in Hungary was fortunate to find a haven from the cataclysm about to unfold in Europe.

Within three days of his arrival in La Paz, Pál was hired by the Iturralde brothers, pioneering architects and builders, who dreamed of bringing modernism to Bolivia. Pál started as a draftsman in their company and quickly rose though the ranks. So grateful were the Iturraldes for Pál ’s training in statics (the forces acting on multi-story buildings) that they gave him a large apartment on the top floor of their own building, which also housed company headquarters.

My initial interest in this building it was because it was my parents’ first real home. But there’s another reason it’s worth looking at: Historians of architecture that I have interviewed in La Paz all refer to it is their country’s first “rationalist” (i.e. modernist) building. (They use the word “rationalist” more or less as a synonym for “modernist” since modernism adheres to the “rational” conservation of space and materials.)

The building, also known as El Atelier, was designed and built by Pál ’s employer, Luis Iturralde. Luis had spent his formative years in France and had studied under the great Architect Auguste Perret who also taught Le Corbusier as a young man. Perret was the foremost authority on reinforced concrete construction. Iturralde returned to Bolivia in 1930 determined to bring the ideas and principals he had learned in France to his isolated nation. His wealthy family gave him a piece of land to build on, on what was then the edge of the city. But his dream of building the first modernist multi-story building in La Paz was not so easy to realize. The principal obstacle: Cement did not yet exist in Bolivia so working in reinforced concrete was impossible. Undeterred, Iturralde set about using available materials to devise a structure that would at least look like a modern, reinforced concrete building.

For example, for beams to support the building’s floors he used steel rails salvaged from a tram line that had been decommissioned.

In the end the building had only four stories, not five as Iturralde had dreamed, but it was high enough to outrage the local gentry who claimed it was sacrilege to erect a structure which, from a certain angle, blocked the view of Illimani, the Andean peak soaring above the city. By naming the building El Atelier, Iturralde was paying homage to Le Corbusier whose Parisian atelier was the prime locus of modernist architecture. When Pál came to work in the Iturralde’s office in1939 he was aware of the irony: El Atelier was a building that pretended to be something that it wasn’t. If this weren’t bad enough it was an homage to Le Corbusier who had vigorously fought against what it represented, namely the old ruse of using materials to emulate other materials in the name of style.

But seen from another perspective El Atelier was an extraordinary achievement, achieved with great persistence and ingenuity. The story of the Bolivia’s first modernist building as well as my parent’s first home is continued in the video letter from La Paz, Bolivia, both past and present.

BOLIVIA’S FIRST MODERNIST BUILDIING from MOIRA PRODUCTIONS on Vimeo.

Jane Lucas

January 9, 2022 at 4:25 pmJust came across this piece. Not sure how. Enjoyed it as a glimpse of your family’s interesting history.

Danuta

December 19, 2021 at 12:00 pmInteresting! Thank you for this post. The stories like that need to be remembered.

Jorge (Coco) Velasco

March 12, 2021 at 8:19 pmi have learned more about you in your other blog and in Luis Iturralde’s Book. I shared your site in a Facebook group (900 members) that deals with buildings before 1950 and it was quite a success

All the best

Coco

Jorge (Coco) Velasco

March 11, 2021 at 6:09 pmNice story and Video. My father Jorge Velasco and uncle Néstor Velasco in the picture i believe we’re partners os Soconal at the time What I was Pouki’s name and you name? I am writing a book about a Hungarian escaping at the end of the war who will eventually arrive in Bolivia so your fathers story interests me

Tom Weidlinger

May 4, 2021 at 7:08 pmHello Jorge:

I just saw some of your comments from a couple of months ago. If you write me directly to the email contact on the website I will try to answer any questions you may have.

Tom