From the childhood of the Restless Hungarian…

The Hungarian word for motion picture theater, mozi, was coined in 1907. The American word movie came into usage one year later. Movies came early to Budapest. The pomp and circumstance of royalty was a popular topic in the first Hungarian newsreels.

Otto von Habsburg, the last crown prince of Austria Hungary, appears, at age of five, in a newsreel with his mother Zita, Queen of Hungary and Bohemia and the last Empress of Austria. Accompanied by dozens of ladies and gentlemen in waiting, they have just attended church in the town of Várpalota in western Hungary.

We see a procession of high clergy in full regalia. Standing to attention are hussars with ceremonial lances and plumed hats. Liverymen in brocade coats assist ladies with long trains into their coaches. Postilion riders with are mounted on caparisoned horses.

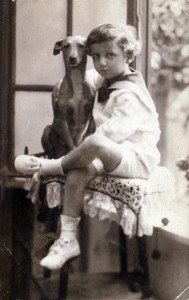

Shooting through a coach window we see the young prince lifted into his seat. For just a few frames we see him clearly: a sweet longhaired boy wearing a tunic with a wide white collar.

I have portraits of my father, at the same tender age, with the same hair and the same clothes. I can imagine my grandparents, Andor and Julia Weidlinger, seeing this newsreel film in the local movie theater in the Elizabeth district. Royalty was the subject of endless fascination. Little Lord Fauntleroy, the sweet aristocratic hero of a children’s novel, was as famous as Harry Potter. His long golden locks, cutaway velvet jacket, and blouse with a frilly collar became a model for children’s fashion among the upper middle classes in both Europe and the United States. In the1918 Hungarian film adaptation of Little Lord Fauntleroy, the child star, Tibor Lubinszky, looks a lot like my father.

It makes perfect sense that Paul’s parents dressed him as a young lord. They could not be admitted to the inner circles of Hungary’s aristocracy yet they aspired to live life just as well.

The yearning for status of middle class Jews is manifest in the Sunday afternoon promenades of fashionable people on two parallel boulevards in the Budapest during the years just prior to World War One. On Vaci street, well-heeled gentry, gallants and their lady consorts strolled to see and be seen. On nearby Crown Prince Street a similar ritual unfolded but with one significant difference: The Crown Prince Street gentlefolk were Jews. The Vaci Street people were not. Jewish satirists, especially those who were sympathetic to the plight of the working class, lampooned their brethren for aping the manners and customs of the aristocracy.

I don’t know that Andor and Julia took part in these promenades but I do know that they had the firm expectation that their son’s education, accomplishments, and wealth would surpass their own. At the age of three my father had his future all planned out for him.