Early in 1961 Paul Weidlinger received an urgent call from the architect Marcel Breuer. Something had gone horribly wrong during the construction of the Abbey Church that Breuer had designed for the community of Benedictine Monks in Collegeville, Minnesota.

Breuer, like my father, was Hungarian. Both were influenced by the Bauhaus Movement and they knew each other socially. In fact it was Breuer who had persuaded my father to build a summer home on Cape Cod, near Breuer’s own house. But almost ten years passed before the famous architect consulted with Paul on a professional matter.

Breuer’s design of the St. John’s Abbey Church called for a zig-zag, folded plate concrete roof covering a very large span. But as soon as the forms were removed cracks began to appear in the concrete. It seemed possible that the roof could fail if construction shoring were removed.

Paul and his young partner, Matthys Levy, studied the original plans and realized that the engineer on the job had not provided sufficient reinforcing. Levy recalls: “We came up with a scheme of post-tensioning; applying cables that pushed the thing up from the bottom, at the center, to keep it from falling.”

Bob Gatje, Breuer’s biographer, as well as an architect working in his office at the time, told me: “The near failure of the abbey folded plates was a terrible affair – kept completely confidential within the office and at the Abbey. Jim Leon, the design engineer … had been a personal favorite of Breuer’s so it was difficult for Lajkó (Breuer) to accept the fact of his errors and to abandon him in future. But your Dad and Matt had saved the day and they became our favorite engineers for ever after.”

No one had heard of Paul Weidlinger or Matthys Levy when I arrived at the Abbey to film the church.

The structure is radical. Breuer’s work is sometimes described as Brutalist. The term ‘Brutalism’ does not derive straight from the word “brutal”, but originates from the French béton brut, or “raw concrete.” Brutalist architecture, descended from the modernist movement of the early 20th century, tends to be fortress-like and massive. Brutalism is sometimes seen as a reaction by a younger generation to the lightness and “frivolity” of some 1930s and 1940s architecture. In one critical appraisal (Reyner Banham) Brutalism was seen as an expression of moral seriousness.

Before arriving in Collegeville I simply could not conceive of a Brutalist church that would work. Churches are not supposed to be fortresses. Coming upon the church on a rainy day at the end of a long avenue, my first impression was not one of being welcomed by the structure but rather intimidated by it. But then I went inside and my sense of the space changed. Watch the video.

Marcel Breuer’s St. John’s Abbey Church from Arc Light Digital Media on Vimeo.

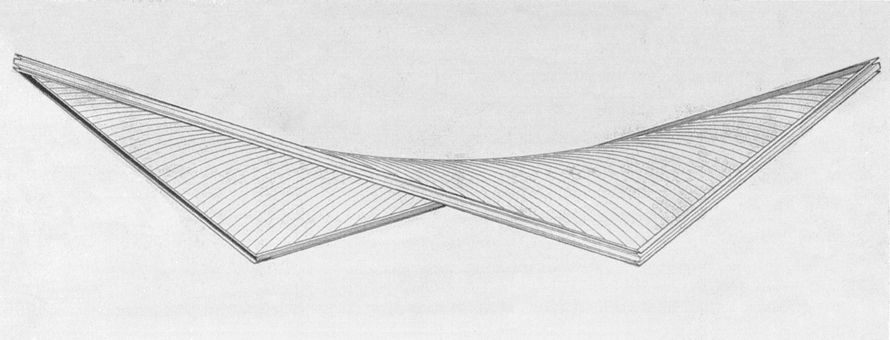

Just three years later Breuer won the commission to design a second church, this time for the Catholic parish of Norton Shores, Michigan. Paul and Matthys were the engineers from the start. St. Francis de Sales has features in common with St. Johns, as you will see in the video, but the sidewalls, instead of being folded like an accordion, are hyperbolic paraboloids.

A hyperbolic paraboloid is a saddle-shaped form which follows a convex curve about one axis and a concave curve about the other. In buildings hyperbolic paraboloids are mostly used for roofs. Breuer’s use of them for sidewalls is quite unusual and purely sculptural; the weight of the roof is supported not by the sides but by the inward-slanting front and rear walls. Local concrete contractors declined to bid on the job, intimidated by the complex curvature of the structure.

A contractor from Chicago, a devout Catholic who had always dreamed of working on a Breuer building, took it on. The budget was one million dollars, a huge sum in those days, but there was very little profit margin. It was largely a labor of love.

Constructed between 1964 and 1966 the job required hand crafted wooden forms that used half a million board feet of lumber. There were 210 separate concrete pours. Overall 7,000 cubic yards of concrete were used, reinforced by 575 tons of steel.

How did such a radical structure, so unlike what churches historically look like, come to be accepted by a small mid-western parish in the 1960s? I spoke with Mary Ann Howe, one of the parishioners. She was a young mother at the time and very involved in the life of the church.

Marcel Breuer’s St. Francis de Sales Church from Arc Light Digital Media on Vimeo.

Georgia Wright

September 19, 2014 at 1:12 amA lovely job, Tom. As a St Paulite, I’ve visited the Walker and found it wonderful. I wanted to see Collegeville but never seem to have made the trip. Bad me!

You do fantastic work!

Georgia