A few months ago I wrote about the new film project I am working on, Keep On Moving Forward, The Story of Emma’s Revolution. I want to thank all of you who generously supported the project already, including at our valentine “For The Love of Justice” fundraiser. That event netted around $16,000 and, together with an additional $4000 raised, put us well on the way to realizing out $50,000 goal to cover expenses for the rough-cut of the film.

A few months ago I wrote about the new film project I am working on, Keep On Moving Forward, The Story of Emma’s Revolution. I want to thank all of you who generously supported the project already, including at our valentine “For The Love of Justice” fundraiser. That event netted around $16,000 and, together with an additional $4000 raised, put us well on the way to realizing out $50,000 goal to cover expenses for the rough-cut of the film.

A few days after the event I embarked on an east coast road trip from Miami to Boston to interview people on camera. With the help of my friend and volunteer sound person, Drew Thilmany, I interviewed twenty-eight people in eighteen days. We talked to Pat’s sisters, Sandy’s family, labor organizers, folk singers, social justice activists, radio show hosts, a church minister, and friends and colleagues who have known the Emmas in all the chapters of their lives. Some of you will know the names of Sonny Ochs, Reggie Harris, Greg Greenway, and Elise Bryant. We were also very happy that, at the last moment we were able to get an interview with Amy Goodman of Democracy Now.

The typical structure of films about performing artists is a trajectory from obscurity to celebrity, with adulation, money, hubris, drugs, sex, scandal and redemption in rapid succession. Try to fit Pat and Sandy into that time-honored plot line and you quickly realize that’s not their story. In my conversations with folks on the road there was no whiff of anything scandalous or salacious. Rather I learned about a powerful social justice community and about the work of giving voice to those who are not seen and marginalized.

Many days lie ahead, sifting through the material we shot. It’s too early to summarize. But I want to tell you about the interviews we did with family.

I wanted to know: How were Pat and Sandy shaped by their families? Did rebellion against their family’s’ values and culture play a role? Were there clues in childhood that point to the people they would become?

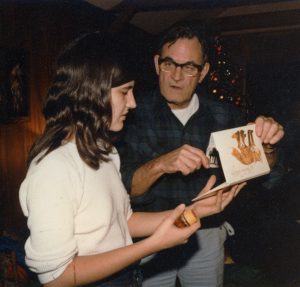

Sandy’s parents, Dave and Judy Opatow, welcomed us at their modest apartment in South Miami. Her older sister Jessica flew down from Long Island with photographs which we laid out on the kitchen table. Here is what they said:

Sandy was the good kid. She talked before she walked and she had a lot to say. She had a strong sense of fairness at an early age. Jessica tells how, when the family sat down at the kitchen table to play the board gave of Life, Sandy quickly sussed out a fundamental design flaw. The game was stacked. “When you spun the dial it gave you a profession; if you got to be doctor, you couldn’t be beat. You’d get $20,000 each time you landed on your paycheck, more than any other profession. Sandy decreed that everyone would be a journalist and make $10,000.

Later she told her mother that opera was the only kind of music that she hated because it seemed that every plot required the death of a woman.

Dave said his daughter was an intense student. In a third grade class for high-achieving students she became so anxious over a ridiculously impossible homework assignment that she started pulling her hair out. Older sister Jessica said it was scary to see.

Librarians by profession, Dave and Judy loved music. The Fireside Book of Folk Songs was the family bible, Dave could pick up and play almost any instrument, and on Sundays Judy played the organ at a local church. The whole family (including younger brother Mark) sang effortlessly, in perfect harmony. Everyone knew the lyrics to the songs in the Beatles album, Rubber Soul. Jessica observed, “It was the soundtrack to our lives.”

In 1994, Sandy wrote a song called, Grandma’s Piano, that speaks to the legacy of music in her family:

When I think about my childhood, there was music everywhere

My older sister’s rock ‘n’ roll would often fill the air

On family trips we’d all sing rounds and make up silly songs

Our voices were in harmony even when we didn’t get along

From my grandma’s piano came the sounds I learned to love

From my grandma’s piano the beauty of music was enough

As my mom and dad would play together

Songs that will stay with me forever

They still sit and play upon my grandma’s piano

Sandy was a senior in high school in 1984. While Jessica was getting into trouble and smoking marijuana, Sandy was still the good kid, not rebellious, and definitely not part of the counter-culture. She was popular, but not in an obnoxious way. She was a snazzy dresser and had a clean-cut boyfriend who was also happened to be a nice guy. There are pictures of them on prom night, getting into a limo. Sandy looks like a 1970s Vogue model, wearing retro white sheath.

Only after she started college did her wardrobe morph from chic to groovy. She started wearing anti-apartheid tee shirts and going to reproductive rights demonstrations. More evidence of the Sandy who would become half of a singing duo named for the famous anarchist, Emma Goldman.

The last question that I asked Dave and Judy was how they felt about the political messages in the music of Emma’s Revolution. Judy said, smiling, “We have a rule in our family never to talk about politics.”

“Why?” I ask.

“Because we want to remain a family.

Pat is one of six sisters whose birthdays span twenty years. Three of them gathered to meet with me at Jackie Fisher’s house on an inland lagoon in a town north of Miami. Tammy, two years younger than Pat, has the most vivid memories of their shared childhood. She describes herself as a timid child, who adored her big sister, and was often protected by her.

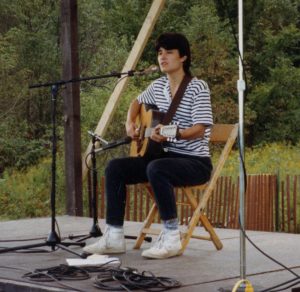

In middle school Tammy and Pat auditioned and were accepted into The Singing Angels, a Cleveland children’s’ choir with a rigorous rehearsal and performance schedule. Their parents John and Elsie (now passed away) were supportive of their daughters’ music. Later, when Pat did gigs as a teenager in local coffee houses and pubs, they’d proudly sit through their daughter’s performance, nursing a pitcher of beer.

Pat’s written two songs, Jaime (1993) and Let Her Go (1999) about her parents and, in particular, her father. I didn’t know there was a third song. Tammy got out an old cassette tape played and we all listened to it. Making Peace has never been published and may exist only on that tape. It seemed important for Tammy to play it, in the presence of her older sisters, Sharon and Jackie.

I think about my dad and the years that we’ve crossed

I look at him and realize he’s the only one I’ve got

I look into the mirror and I see him looking back

I ultimately smile and I rail at the fact

And love is never perfect but it grows…

Tammy was tearful as we listened and Sharon and Jackie looked very grave.

Tammy: We had a bundle of old-time wooden yardsticks in the closet. I asked my mom about them. She said dad would get so mad they made an agreement that that’s what he would use to spank you because they would break before they did any real damage.

Sharon: Once my twin sister, pushed him over the edge and he literally threw her around and I threatened to call the police. We were young teenagers. It scared the hell out of me.

Jackie: I do remember Pat, distinctly. She would bump heads a lot with dad.

Tammy: Dad would not tolerate the mouthing off. He would get up, and then you knew you needed to move away, fast. Pat would stand up for me when he would yell at me and then I would exit. I was protected. Then she would mouth off to him.

I sensed in Tammy a yearning to reach a consensus with her older sisters that might be officially recorded, on camera. She mentioned that John Humphries had been good and generous towards many people. I believe she wanted a collective assertion that the good outweighed the bad in their experience of their father.

Tammy: He didn’t want to be that way.

Sharon: He was flawed.

Tammy: He was in pain.

Sharon: [In the song] she understands his pain and realizes it was maybe something that is reflected on how he treated her. That’s really deep.

I spoke with Pat about this after I got home from the East Coast shoot. She told me that she wrote this song in order to come to terms with her feelings about her father when he had a stroke and they didn’t know if he would survive.

Years ago when Pat played Making Peace for her sisters Karen and Sandy (they were not present at our interview) they were upset. They had suffered their father’s abuse most deeply and they shared disturbing details. “You are going to easy on him,” they said. Pat never sang the song again.

In another song about her father, Let Her Go, Pat writes and sings in her father’s voice, telling his own story. He loses his own mother at the age of four, in the 1919 flu epidemic and grows up to live a hard life.

Let her go, Let her go

As the tears and sorrow flow.

Restore this soul within me.

Free my heart and let her go.

In the penultimate stanza he says:

I married in the city. I worked and raised a family.

I saw my mother’s image in my wife and daughter’s eyes

I felt the rage within me well up and burn right through me

My love for them was true but I could only criticize.

For me personally, this song has resonance. My own father’s mother died when he was four, in the same influenza epidemic and he too carried trauma which was passed on.

A couple of weeks later, near the end of our East Coast road trip, Drew and I had the pleasure of staying with Sonny Ochs, who has been a friend and mentor to Pat since the 1980s. Over the years Pat, and then Pat and Sandy, have often joined a community of performers who go on tour annually to perform the songs and celebrate the legacy of Sonny’s bother, the legendary folk singer Phil Ochs.

When I asked Sonny to name her favorite Pat Humphries song I was surprised that she chose Jamie. I’d only heard it once before. Sonny played it to refresh my memory.

There’s a frightened little girl inside this woman’s body

Jamie won’t you go to bed early

For this child didn’t get to be a child for long

Tomorrow’s gonna be a brighter dayI’d heard his threats to my mother in the kitchen

Jamie won’t you go to bed early

You wouldn’t get hit if you kept your mouth shut

Tomorrow’s gonna be a brighter dayI learned if I’m not perfect then I shouldn’t be loved

Jamie won’t you go to bed early

I tried my best but it was never enough

Tomorrow’s gonna be a brighter day

The song is raw. Pat sings without accompaniment. I asked Sonny why she chose this song. “Because women and children who are subjected to domestic violence need to hear it.” They need to be seen and heard.

NancyParmet-Stitham

June 13, 2023 at 10:01 pmI have known Pat for more than 30

years, and Sandy for quite some time as well. We all met at a camp

Called “Fieldston Outdoors” and have shared many special times together. When I lost my husband in April 1998 Pat played at his funeral. My daughter Hayley, and my partner Bill were at the beautiful event that you had a year ago in the Berkeley Hills.