Paul Weidlinger died of a stroke at eighty-five. At sixty-five I have been having intimations of mortality. I wrote about the passing of our dear friend, David, quite unexpectedly three weeks ago. His brain bleed started with a slight headache, nothing he thought he should be worried about until it was too late. I thought of this two days ago when Sharon and I headed up Route 4 to go on a day hike in the mountains. The change in altitude made me unexpectedly dizzy and I felt a pressure on my face. Then we noticed that left side of my face had turned downward, drooping . The droop only lasted about five minutes, but after Dave’s death we had made a pact to take even small warnings seriously, so we drove to the emergency room. By the time we got there, I was feeling just fine and was just a little embarrassed by the huge fuss they made over me. Bottom line: Drooping is not good. It’s a symptom of a TIA, a transient ischemic attack, or mini-stroke. Never mind that I had no other symptoms, slurred speech or weakness in my limbs. I was given blood tests, an electrocardiogram, and a cat scan and sent home with a prescription for blood thinners. Two days later I had a brain MRI, a sonogram of the carotid arteries, and an echocardiogram. Nothing showed up on these tests.

Then I went to see my GP, a plain speaking woman who has known me for several years. I argued with her that my alleged TIA was a fiction, just some weird manifestation of sinus pressure acting on the facial nerve. She wasn’t buying it. I’d had a stroke. Now I had to take measures to reduce the chances of my “having the big one.” My doc said: “You take good care. You don’t want to wind up with Sharon wiping your ass.” She scared me. I think I needed to be scared.

I am vulnerable. That’s an existential fact. Living, breathing humans are vulnerable. Just now I am thinking especially of our neighbors to the north, in Paradise, California, who lost their homes in the Camp Fire. And I am thinking of friends in the Bay Area who inhaled the smoke from that fire day after day until the blessed first rain of the season came to wash the air clean.

We are all vulnerable. Thinking this makes me take stock of the precious life that I have. I hope to live as long as my father did. I met Sharon just four years ago and we still have much to do together on this earth.

The Restless Hungarian is also something I had to do, an internal imperative, and something I am still doing as the book goes to publication and I transition back to working on the film. Excavating, understanding, and telling the story of my father has been a huge undertaking—longer, harder, more rewarding and completely different from anything I have done before. It hasn’t been to pay tribute to my dad or to prove anything. It is a work of making meaning.

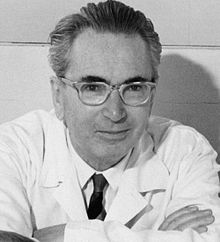

To explain what I mean by making meaning I refer to Viktor Frankl, the Jewish neurologist and psychiatrist who survived Auschwitz, found meaning under the most horrific circumstances, and conceived of Logotherapy, a humanistic approach to psychotherapy that does not pathologize the patient. I first read Frankl’s book, Man’s Search for Meaning, as a teenager and was completely in awe of the courage of the man who wrote it. I read it again recently and, except for the fact that the author (a product of his time) uses the masculine pronoun to refer to everyone, it still speaks to me. I’ve taken the liberty of replacing “he” and “him” with “she” and “her” as appropriate.

Excerpt from Man’s Search For Meaning

I doubt whether a doctor can answer this question in general terms. For the meaning of life differs from person to person, from day to day, and from hour to hour. What matters, therefore, is not the meaning of life in general but rather the specific meaning of a person’s life at a given moment. To put the question in general terms would be comparable to the question posed to a chess champion: “Tell me master, what is the best move in the world?” There is no such thing as the best or even a good move apart from a particular situation in a game and the particular personality of one’s opponent. The same holds for human existence. One should not search for an abstract meaning in life. Everyone has their own specific vocation or mission in life to carry out a concrete assignment, which demands fulfillment. Therein one cannot be replaced, nor can one’s life be repeated. Thus everyone’s task is as unique as the specific opportunity to implement it.

My father made meaning in his life through his work. As a young man he struggled to formulate his personal vision of Modernism, which he called the Joy of Space, the subject of the next post.

Barry STONE

February 2, 2019 at 5:30 pmI wish you a great journey Tom and Sharon.

I also wish I could find the lonk that you sent

Holly C.

December 1, 2018 at 3:36 amWow, Tom, I am glad you are okay and didn’t suffer a worse problem! I’ve had migraines since young adulthood; they freaked my dad out because his mother died suddenly and unexpectedly of an aneurism. Thankfully, my headaches were diagnosed as true migraines. They suck, but are unlikely to kill me. But something else will! As you say, we are all vulnerable. Do take good care of yourself, and I hope you and Sharon have many, many more happy years together.