I visit a remote railroad station looking for clues regarding my parent’s immigration to Bolivia in 1939. The video at the end of the blog post documents the journey.

My father never admitted to me that he was a Jew. This fact, as well as his denial, is important subtext in the story of his life, explaining key developments that otherwise make no sense. One of these was his immigration to Bolivia in March 1939. It was not a destination for a budding young architect with some of the best training Europe could offer. It was, however, one of the few options for refugees fleeing the continent after Hitler’s invasion of Austria and Kristallnacht (the “Night of Broken Glass”) when the persecution of Jews turned violent in Germany on a mass scale. Bolivia accepted about 20,000 Jewish refugees with technical and agricultural training. Paul Weidlinger was one of them. But like many assimilated Hungarian Jews of his generation, he did not identify as a Jew. Nor did he think of himself as a refugee, despite the fact that he was expelled by authorities from both England and France and was barred from working in his native Hungary because of his arrest record as a communist.

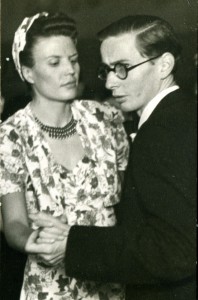

Paul did well in Bolivia. Last month’s post Bolivia’s First Modernist Building attests to this. Parenthetically, my mother who followed him across the Atlantic and married him in La Paz was not a Jew. But like many of the Europeans who came here, she found it hard to adapt to the climate and culture of the land. Though she lived in Bolivia for only four years, it had a lasting impact on her psyche and her sense of self in the world.

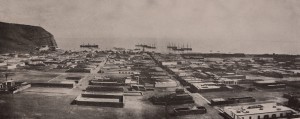

I wanted to learn how their story fit into the larger historical canvas. This is what brought me to Charaña, the place where my parents and thousands of other Jewish refugees first set foot on Bolivian soil. Charaña was a station on the railroad between the Chilean seaport of Arica and La Paz.

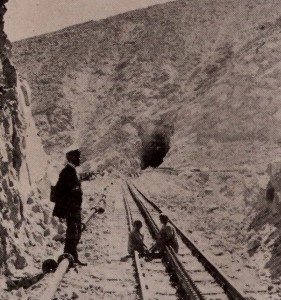

In 1939 and 1940 almost all European refugees came through Charaña. The train climbed from sea level to 14,500 feet up the desolate flank of the Andes’ Cordillera Occidental. The route was so steep that for part of the way a special cogwheel locomotive was needed to engage cogs in a center third rail.

A children’s ditty that was sung in both Chile and Bolivia about this train went:

Arica La Paz, La Paz, La Paz, Tres pasos p’atrás, p’atrás p’atrás. Arica La Paz, La Paz, La Paz. Three steps back, back, back.

Three steps back may refer to the actual slippage of the train itself as poor maintenance, landslides, and worn cog-rails impeded the train on its long climb.

What was the refugee experience? Chilean authorities chose Arica as the port of disembarkation for European refugees because of its isolation. Surrounded by desert with no roads connecting it to other towns, it was impossible for refugees to choose to remain in Chile without papers. The only access was by sea, air, or the train, which headed to Bolivia in the interior. The train journey to La Paz took two days.

On April 29, 1939 my mother wrote to my father from Arica:

Dearest, I am here now. I have only one wish: to be in your arms. Just a few more days and then that will come true. I received all of your letters, and I believed only what you wrote to me and followed your advice. And it all went well. I still don’t know how and when I will travel. Give me some advice, please. On Monday there is a train, though no tickets with sleeping accommodations. There is a plane on Tuesday, which would only take an hour and twenty minutes, but it costs $35 American. Or I can wait another week and travel on Monday in eight days; such a long time without you does not work for me.

Thirty-five American dollars was beyond my parents’ means, so my mother took the train. The journey was completely unlike anything she had experienced. Refugees Heinz and Hanni Pinshower, following the same route a few months later, described their journey to the interior:

We absolutely didn’t know what was awaiting us. We didn’t know about the people, their customs or traditions. We did not expect the altitude to be so oppressive. On the train from Arica to La Paz, peoples’ noses and ears were bleeding. The Indio. We never had seen anything like them. Already on the train, at stops, a real novelty; we looked at them; they looked at us.

We looked at them; they looked at us. My mother took many pictures of Indians with her 35mm Leica camera, her most prized possession. As with most images recorded by Europeans, one rarely finds Indians and whites within the same frame, in the same space. The separation is palpable. The image below is an exception that underscores the rule.

The long climb from the sea ended when the train crossed the Bolivian frontier at Charaña. Here the twin snow-capped peaks of Pomerape and Parinacota rise from the desert like sentinels. Charaña was a Rubicon; there was no turning back. Not only was it a frontier outpost, but a demarcation point between an old life and a new. For this reason I was determined to go there to see what echoes of the past might be felt. I assumed this would be easy. It was not.

To get to Charaña I hired a guide and a driver with a four-wheel drive vehicle at an exorbitant price. Smugglers, bringing electronic goods and other high-end consumer items from Chile, use the same route and pay high prices for transport. At $250 a day our cramped, rattling jeep was a bargain. The pavement ended at the industrial town of Viacha, west of La Paz. After that it was 150 kilometers of bone jarring dirt roads at 13,000 feet, across one of the highest deserts in the world. The tiny villages that we passed were poor, struggling examples of subsistence agriculture and animal husbandry at the most basic level.

The monotony and anxiety of the trip (that we might breakdown, run out of gas, get lost, etc.) was broken by stops to shoot landscapes, llama and vicuña herds as well as re-tie the baggage on top of the jeep that kept getting shaken loose. On one of these stops I noticed that the valve on the oxygen tank that I had brought along had been jarred open and the tank was empty. We planned to spend the night in the desert. The oxygen would have allowed me to sleep, since I struggled with altitude-induced sleep apnea.

About four o’clock in the afternoon, after having passed the forth anti-smuggler police checkpoint, the first sign of Charaña was a mile of rubbish, mostly plastic bags, snagged on the desert rocks and brush. The town itself was an unpaved grid of ten square blocks of brick and adobe houses, most of them unfinished.

And then on the far edge of town… railroad tracks. I did not think I would find them because they are not visible on Google Earth. I had assumed that once the railroad stopped running the steel would be considered too valuable to be left in the desert. Not only were there tracks, but the tracks led to a train yard and a seemingly abandoned station, like a set from an old Western movie.

Had my mother and father briefly disembarked here and showed their precious Bolivian visas to the border guards while the cogwheel locomotive was being shunted? What did they feel as they crossed this Rubicon, overlooked by the mountain twins, Pomerape and Parinacota?

What did thousands of other refugees who came this way experience at this moment: relief, anxiety, disorientation?

Walking the tracks with Chile at my back, I mused out loud to my camera in much the same way I am writing here… but on the soundtrack I am breathing hard from the altitude. Perhaps the experience of breathlessness, both literal and metaphorical, is the echo of the past that I was seeking. Play the video below.

micha x.

November 15, 2018 at 9:13 pmTom, love your meandering story-telling style. This chapter left me wondering about two things – perhaps your vast research has given you insights:

• Landlocked Bolivia still imports much through Arica (which used to be Bolivian territory, BTW). But you tell us the railroad is no longer used. How are the goods transported these days and why was the railroad no longer an option?

• Jewish immigration to Bolivia: have they made any mark on the country (as they have in neighboring Argentina)? Any famous (as least in Bolivia) Jewish Bolivians?

Tom Weidlinger

November 20, 2018 at 12:27 amMicha: There is a simmering border dispute between Bolivia and Chile that has gone on for decades. I do not know why the railroad was discontinued… but I suspect it has something to do with this. There is a thriving black market trade with smugglers bring appliances and electronics from Chile into Bolivia… by road.

No famous Jewish Bolivians that I know of but maybe someone will read this post and enlighten us! While I was in La Paz, I reached out to representatives of the Jewish community there, which is now much smaller than it used to be. An excellent book about Holocaust refugees to this country is HOTEL BOLIVIA, by Leo Spitzer.

lwhitcheck

September 30, 2015 at 9:23 pmThank you Tom for reporting on your Dad’s and your amazing journeys! This chapter was particularly eyeopening as well as poignant. And, oh so relevant to the world we live in…