When I was very young, on my first job as a producer and director, I was dispatched to Prague, Czechoslovakia, to produce some dramatic recreations from the life of the 17th century astronomer, Johannes Kepler, for the PBS television series Cosmos. The year was 1978 and Czechoslovakia was firmly under the thumb of communist hegemony. The Soviet invasion of 1968 had put an end to Prague Spring, the brief period during which the government of Alexander Dubcek had introduced political and economic reforms, freedom of speech and amnesty for political dissidents.

Eight years later Prague was a very somber and dark place. It was the perfect location to film scenes from the life of Kepler. It was also incredibly cheap. American dollars paid for actors, extras, extravagant costumes and props, and locations – cobblestone streets, a castle, and 17th century interiors at a mere fraction of what whey would have cost in the West. I couldn’t believe how fortunate I was to be directing these lavish scenes just one year out of film school.

At the same time simply being in Czechoslovakia was nerve wracking. We were constantly under the surveillance of the ŠtB, (State security police). All hotel rooms where foreigners stayed were bugged and we had to be careful not to embarrass or compromise our Czech hosts with questions or comments that could be interpreted as political. One of the Czech actors knocked on my hotel room door in the middle of the night to ask me if I could somehow aid in smuggling him out of the country. I knew enough by then to realize he was an agent provocateur. On the other hand I could not help but feel a deep sadness, a sorrow for the actors, craftspeople, and technicians who were all too happy to work for me, a twenty-five year old director, who knew far less of his craft and life than they did. We were Americans, a precious link with the West.

Over the years I kept in touch with Jiří Ježek, my Czech production manager. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 Jiří had requisitioned film crews to document The Velvet Revolution, the massive demonstrations and general strike that brought down the communist government in Czechoslovakia. We met in Paris in 1990 where I was working on a film about De Gaulle. Jiří talked about the euphoria of the crowds in the streets of Prague, a collective sense of freedom, and the lifting of a pervasive fear and depression that seemed to dominate life under communism. We wondered aloud about what freedom, democracy, and a free market economy would bring. Would the future that people dreamed of become manifest?

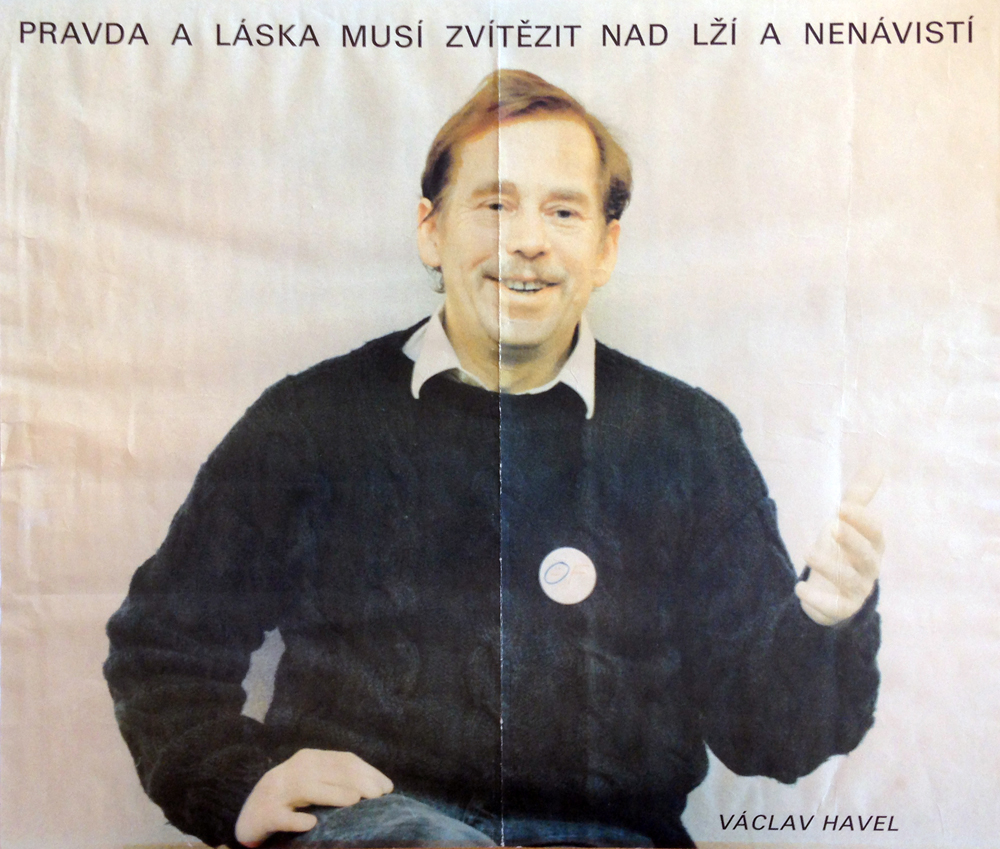

It was then that we decided to collaborate on a film, After The Velvet Revolution, that would follow individual Czechs and Slovaks over time to see how and to what extent their experience would match their dream of freedom and democracy. I raised money and moved to Prague and spent the better part of three years there making the film. For me, one of the powerful motivations to do the film, were the writings of the Czech dissident playwright, Václav Havel. Havel spent four years in prison for speaking out against the communist regime and was elected president in 1990, in the country’s first free elections in 40 years. I still have an old poster of Havel on my wall from the Velvet Revolution. It has a crease down the middle from when I folded it to put it in my suitcase, coming back to the states. It bears his famous slogan: Pravda a láska musí zvítězit nad lží a nenávistí “Truth and love must prevail over lies and hatred.”

After our current president was elected I made a T-shirt bearing this slogan which I often wear. On the back of the shirt is my name. It identifies me with the slogan. It says, “This is what I, Tom Weidlinger, believe in. This is not advertising. This is not an anonymous post. This is not dogma. This is where I stand, not as a Democrat or Republican, but as a human being.” To wear it feels downright subversive and liberating. I have this fantasy of hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of people wearing this black T-shirt with bold white text, in the streets, shopping malls, cities and small towns of America.

After The Velvet Revolution aired on a few public television stations in 1994. By then the demise of communism and the Soviet bloc was old news and American television programmers knew it would get meager rating points. The film became an orphan without distribution, save for a short run in the educational market.

I never released the feature length version, until now. (It was cut down to an hour for TV.) It’s seems appropriate to put it on the Restless Hungarian blog. It’s not about my father, but it is about the part of the world, Central Europe, that he came from. In the dark days, as a twenty-three year old filmmaker, I stood completely alone on an icy January night, in the middle of Prague’s 15th century Charles Bridge, guarded by baroque statues of saints. For a moment I felt lifted out of time and space and deeply linked to the world of my ancestors. Thirty- eight years later I had an identical experience standing on Budapest’s Chain Bridge, one foggy February morning. Connected.

The original, full-length version of After The Velvet Revolution, is presented here as a mini-series, in four sections, spanning four years of history, released over four consecutive weeks. Enjoy.

Micha Peled

March 29, 2019 at 2:34 amSo far I only watched part 1, but left with a taste for more. Well-short and impressive in range of access. If much is archival it still works seamlessly.

Ovid.tv is a new SVOD platform (by Icarus and Bullfrog Films) that’s looking for content. They probably offer pittance, but it’ll make the film available to a new audience.

My only criticism is that we are not allowed to hear the Czech language – auditory is such a key part of the experience of being anywhere, esp. in another country. The people interested in this film wouldn’t mind reading sub-titles… Cheers.