In last week’s post I wrote about how I came to make the film After The Velvet Revolution. Now I want to share with you some excerpts from a journal that I kept during the early days of the project.

View Part Two here. If you missed Part One, here is the link. Read about the making of the film below.

In the summer of 1990 I met my friend Jiří Ježek in Paris and he described to me what it was like to live through the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia, during the dramatic days of November 1989. First there was fear, fear that the Revolution would not succeed, fear that the demonstrations would continue to be brutally crushed. But as the crowds grew to tens of thousands of people, fear gave way to confidence and then euphoria. A country and its people seem poised on a threshold and all things seemed possible. Dour shop keepers became friendly. Teachers brought awestruck school children to the peaceful , respectful demonstrations that would bring the old regime down. It was said that the only graffitti scrawled on the walls was left there by Western television crews. A political movement called Civic Forum was formed. It’s leaders were students, musicians, actors, and the dissident playwright Václav Havel.

As I listened to Jiři recounting his experience in Wenceslas square I felt powerful emotions. I wished I could have been there. I wanted to experience it for myself. I wanted to feel the intensity of it, perhaps because my own family had been divided by the iron curtain since before I was born. Jiři and I wondered, what would happen next?

This is how our collaboration was born, sitting in my sublet flat in the14th arrondissement drinking cheap wine. To Jiři freedom existed but had not yet been fully felt or tested. It seemed utterly fantastic and incredible that he found himself sitting in a Western city talking to a Western filmmaker about freely collaborating on a project of a political nature. For me there was a wonderful feeling of “rightness” about what we were discussing and imagining.

Weeks passed. I returned to the States and I set about trying to raise seed money for the film. I read most of what Vaclav Havel had written, his plays, his political essays, and the extraordinary collection of letters he wrote from prison to his wife, Olga, between 1978 and 1982. Havel also wrote a definition of hope.

The kind of hope I often think about (especially in situations that are particularly hopeless, such as prison) I understand above all as a state of mind, not a state of the world. Either we have hope within us, or we don’t. . . . Hope is not prognostication. It is an orientation of the spirit, an orientation of the heart. It transcends the world that is immediately experienced, and is anchored somewhere beyond its horizons. . . I feel that its deepest roots are in the transcendental, just as the roots of human responsibility are . . . Hope, in this deep and powerful sense, is not the same as joy that things are going well, or willingness to invest in enterprises that are obviously headed for early success, but rather an ability to work for something because it is good, not just because it stands a chance to succeed. The more unpromising the situation in which we demonstrate hope, the deeper that hope is. Hope is not the same thing as optimism. It is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out .… It is also this hope, above all, that gives us the strength to live and continually to try new things, even in conditions that seem as hopeless as ours do, here and now. — Vaclav Havel, Disturbing the Peace

Havel gave me the hope to move forward with the first film project in my career that was entirely my own, that was not commissioned or funded, and in which I had no one to answer to but myself. I wrote a long letter to Jiři outlining how I thought we might work together. He responded positively. He asked for no guarantees, no money up front. I could have hugged him. It took awhile to raise seed money, but four months later I was on a plane to Prague to audition people for the film and to shoot and edit a ten-minute trailer that could be used to raise funding for the full production.

En route I had a layover at Heathrow airport in one of those generic airport hotels. In limbo, I panicked. I had been waiting so long for this moment, this beginning, which felt like much more than just the start of another film project. Perhaps, upon arriving in Prague, I would discover that everything that I had vividly imagined and which had become so close to my heart would bear no resemblance to the project in Jiři’s mind. Perhaps weeks of blurred faxes, anxious, static-filled phones calls, and Jiři’s imperfect English (not to mention my non-existent Czech) had contributed to some gross misunderstanding that would utterly defeat us. The moment of truth was approaching.

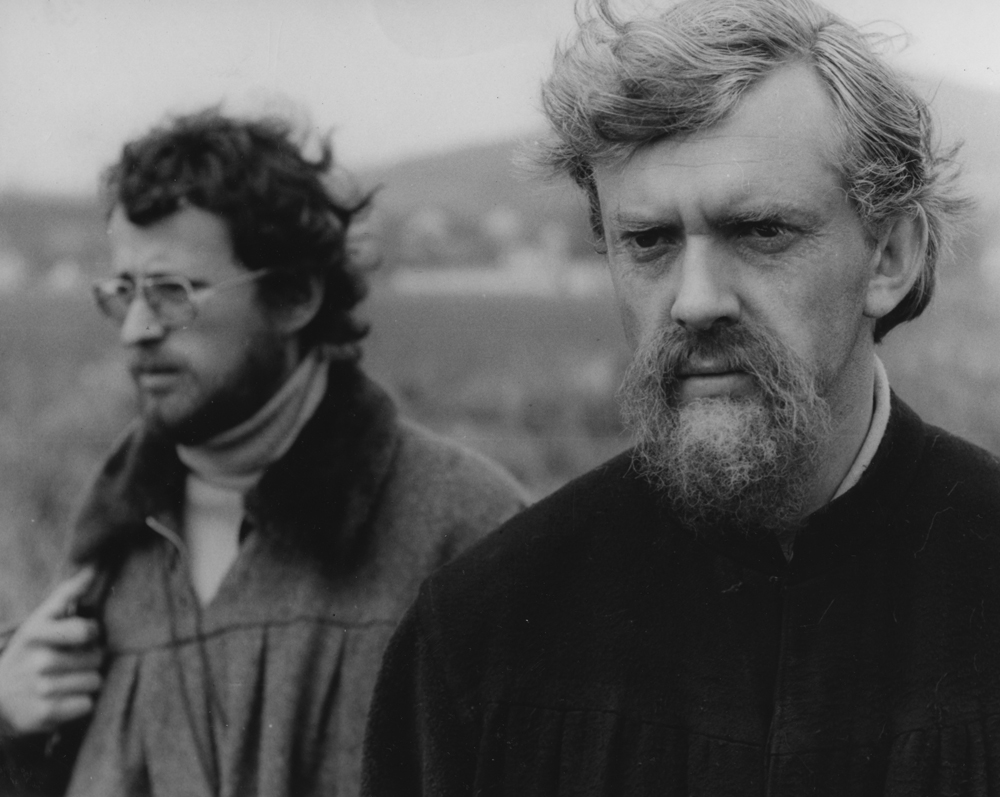

I arrived in Prague under cold cloudy skies. The crumbling airport still looked like it did in 1976. The difference was that the guards at passport control barely glanced at my passport. Jiři was waiting on the other side of the barrier, wearing and old green army jacket and faded jeans. We were both at a loss for words. It seemed what we were embarking on was so huge, so impossibly weighty and important. We walked through Prague’s old town without speaking. There was an acrid smell in the air, the smell of coal that was still the main source of heat for many buildings in the city. On Charles Bridge we passed a man playing a mournful Auld Lang Syne on a penny whistle. Further on the was a mime, more buskers, and hawkers selling wooden Gobachov dolls, Soviet army surplus caps and trinkets from the totalitarian past. I felt my anxieties begin to fade. A quote from another (unknown) Western visitor copied into my journal resonated:

There was nothing to dazzle me in Prague… After being in the West all my life, coming to Prague felt as if some very kind gods somewhere had turned off all the bizarre machinery. All the synthesizers and equalizers, all the laser optics and high-definition loudness, the throbbing bass and the shrill treble all fell miraculously silent. What remained was only a charming old orchestra tune, something curious and comforting. I don’t remember exactly what. It didn’t really matter. I was just relived to be able to hear my thoughts again.

In next week’s post, along with Part Three of After the Velvet Revolution, Jiři and I hold auditions for our film. The contrasts between past and present, expectations for the future and the realities of world in dramatic flux, are manifest in the stories of the people we meet.

Cynthia Eaton

February 10, 2019 at 6:10 pmHi Tom, Thank you for providing a link to Part 1, so I could read and see it too. I was too busy to follow though when it first arrived. What a privilege it is to witness both your creative journey and the unfolding of the Velvet Revolution, 30 years ago. You need to figure out a way to make your t-shirts available, so we can customize them with our own names! This is a VERY well-timed release of this film . . . and thank you so much for making the full-length version available to us in 4 parts through your Blog.I can hardly wait to see parts 3 and 4. You are a masterful documentary storyteller. Many thanks! Cynthia