In last week’s post I shared excerpts from the journal that I kept during the genesis of the project. It was about how Jiří Ježek and I came to conceive and work together on After The Velvet Revolution. This week I’ll share what it was like to start work on the film in Prague.

View Part Three here. If you missed Part One and/or Part Two, click the links. Read on, below.

Jiří put a damper on my initial, rosy impressions of post-Communist Czechoslovakia. When we finally found a table in a crowded restaurant off Wenceslas Square and I began to question him he said with vehemence, “Times are horrible! Freedom is a sweet fruit but it has not brought prosperity. Prices are going up. Wages are being held down.” The air quality readings in Prague were among the worst in the world, due to high dependence on soft brown coal for heating and power plants. Fourteen members of the new federal parliament were expelled when they were discovered to have been agents of the ŠtB, the dreaded State Security Police. Crime was on the increase. (Though later I would discover that the incidences of muggings that seemed absolutely horrific to citizens of Prague would pass without comment in the average Western city.) Yet it struck me that, for all the hardship, Jiří knew he was living in extraordinary times, that history was inexorably moving forward and that people had no choice but the start over again as if immigrants in their own country.

It was time to get to work. Jiří lit a cigarette and though I didn’t smoke I bummed one off of him. Everyone smoked… continously. I figured the only way to work with Jiří and his team was to join them. It couldn’t be much worse than breathing in Prague’s coal-choked air. We needed to make a short trailer that I could use to raise funds for the main project. Jiří proposed to do it in two weeks. We agreed that the central idea of our project was the responsibility of citizens in a democratic society to make a contribution to the functioning of their democracy. We were unapologetically idealistic. The trailer would start with scenes of the revolution that Jiří captured on film in Wenceslas Square, and move on to the first free elections in forty years in which Havel was elected president. Then we’d ask, “What does democracy and a free market economy mean to people in a post-communist world?” Our main task was to find individuals who could not only answer this question eloquently, but also manifest their answers in their lives as we followed them over the coming years. Here are three people who did not wind up in the documentary, but whose stories bear telling:

The very first person I interviewed was Jaroslav Krejčí, a well-known designer and photographer. We were welcomed into his dark apartment with vaulted arches that suggested an ancient wine cellar. Underscoring this impression, Krejčí poured us light white wine from his home in Slovakia. To me he looked like Shakespeare’s Falstaff, a great rumbling bear of a man with a flowing white beard and a black Cossack tunic. With his camera he had documented the Velvet Revolution. “Since then,” he said, half-humorously, “I’ve been asked to do so many photo exhibits that the stress is causing my teeth to fall out.”

Krejčí insisted I sit in a chair from which Jan Patočka, the Czech philosopher, had given clandestine lectures to students in the Underground University. (Patočka died in 1977, after lengthy interrogations by the ŠtB.) Krejčí allowed me hold a precious samizdat book that had been made to honor Patočka. Eighty-eight copies of this forbidden book had been typed out on typewriters and passed from hand to hand because all photocopiers and printers were controlled by the state. Krejčí had added his own hand-drawn decorations to his copy. While I liked Krejčí a lot, I couldn’t envision how he would adapt to life after the revolution, so I did not think he would be a good candidate for the film. His resistance to a repressive regime that not longer existed defined his identity, who he was in the world.

Our next interview was with the co-owner of Prague’s first sex shop. It was located on one of the wide grey boulevards leading out to the airport. Jiří was keen on our doing this interview. I think it appealed to his sense of irony that the first successful private entrepreneurs in this brave new world of free enterprise were hawkers of pornography and vibrators. Ms. X (I didn’t write down her name) was joined by her silent partner, a small narrow-faced man who smiled way too much but said nothing. Ms. X told us that business is brisk. I asked her what she was going to do with all the money she was earning. She said her dream was to fix up a penthouse flat she was the process of acquiring and also to be able to “live at least one month abroad without having to worry about money.” Ms. X already went once a month to Germany to buy sex toys but Paris was the place to relax and breathe. Ms. X had arranged to do her interview with us in front of a life-sized cardboard cutout of a Playboy bunny. She was young and beautiful and aspired to become one of the first Czechoslovak women to grace the pages of the Czech edition of Playboy Magazine. The fee for posing: “Enough to live for a lifetime. “ Despite Jiří’s interest in her story I did not think she was a candidate for the film. The lure of making a ton of money was foremost in a lot of people’s minds, but if that’s all that was on their minds I thought it would make for a rather uninspiring tale over time.

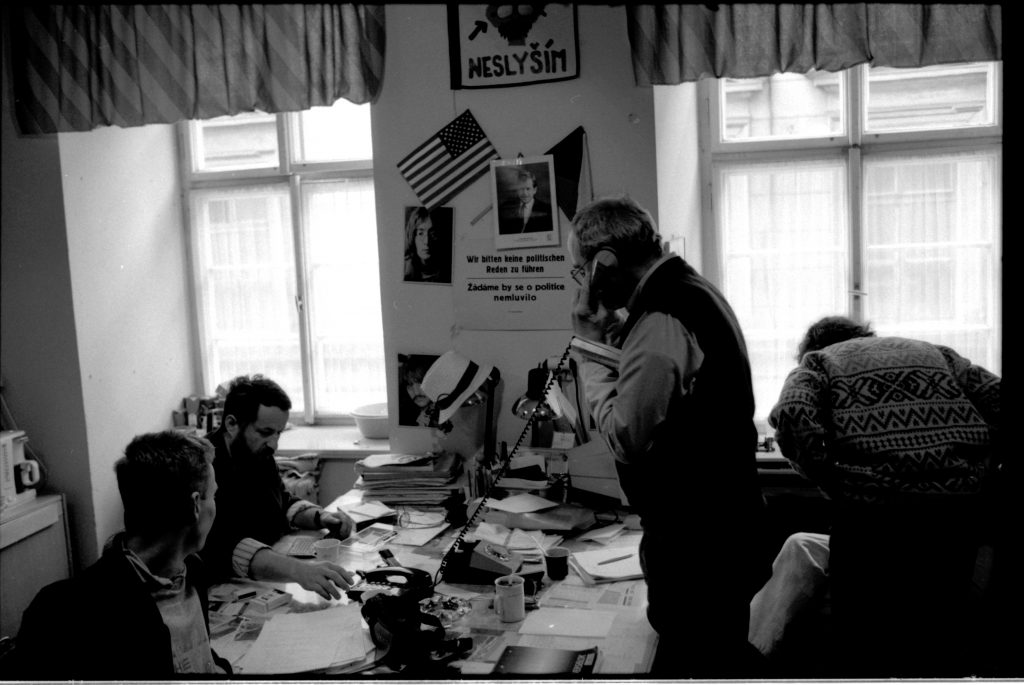

The last person we spoke to on our first day of interviews was found in Prague’s unemployment office. Under the communist regime you were required by law to have a job and your identity card listed your .job and employer. Everyone had a job; even it only paid a pittance. A cradle-to-the-grave social security net ensured that you would not starve but not much more. Now, inefficient state-run factories and agencies that could not turn a profit, let alone cover their costs, were shuttered. Many people were out of work. František Sandanus, a small, neat man with a goatee, was invited to meet with us at Jiří’s busy production office. There was not a lot of space, no free room to meet in, so our interview took place in the midst of convivial pandemonium, as others in the office went about their business. Sandanus talked bitterly about looking for work. “Soon,” he predicted, “people will not have enough to eat and anarchy will break out.” We asked him what his profession was. He told us he was a lawyer, specializing in criminal law. A lawyer? I was truly amazed that someone with his qualifications was found standing in an unemployment line. Then he said something else and it clicked. Sandanus had been employed by the Ministry of The Interior in the old regime. As soon as he said this the big room in Jiří’s office got very quiet. Conversations stopped in mid-sentence. I felt the tension in the air.

The Ministry of The Interior had been Big Brother. It was the agency that hunted, harassed, interrogated and imprisoned dissidents the likes of Havel and Patočka and thousands of less famous persons who had dared to speak out against the communist regime. The rest of our conversation with Mr. Sandanus was listened to by everyone in the room. We proceeded with exaggerated politeness. “What, exactly, did Mr. Sandanus do for the Ministry of The Interior?” He said that regrettably he had been obliged to sign a document stating that he would not discuss his work at the Ministry with anyone for two years.

I pointed out to him that the people who made him sign the document were no longer in power and that President Havel had proclaimed a sort of general amnesty inspired by South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Movement. So why not speak freely?

Sandanus said darkly “Every society has its secret police and its secrets and without keeping certain secrets anarchy would break out.”

I didn’t put Jaroslav Krejčí, Ms. X, and František Sandanus in the film. I wanted to make a film about people who had hope for the future, not only for themselves, but for the world they lived in. However, the circumstances of Krejčí, Ms. X, and Sandanus were a poignant manifestation of the cultural upheaval in the months after the Velvet Revolution.